By AKIN OYEDELE Business Insider Australia

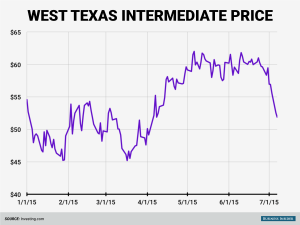

The flop in oil prices this week has been several months in the making.

On Monday, West Texas Intermediate crude oil fell nearly 8% as part of a global sell off in virtually all assets after the Greece referendum results Sunday.

And then on Tuesday, oil prices fell another 4% before regaining some ground in late morning trade.

But even with the reversal, oil is now near a three-month low. Quickly.

For the last couple months, oil had been relatively stable near $US60 per barrel, and it seemed like the worst of the oil crash was over.

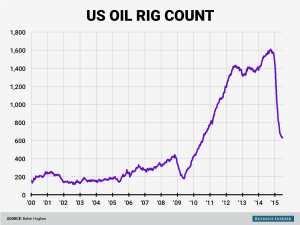

Then last week, the oil rig count turned positive for the first time this year, hinting that perhaps it oil producers were ready to ramp up production with prices seemingly stabilised.

But then on Monday, oil suddenly had its worst day in three months. This tumble, however, was not just about what happened in Greece over the weekend. It had been coming for months.

The Energy Information Administration put out its latest short-term outlook on Tuesday, just in time for an assessment of what’s prompted the most violent move in oil prices that we’ve seen in months.

Here’s the EIA’s analysis of what’s moved crude oil this week, which covers the main catalysts (emphasis added):

“Crude oil prices fell by about $US4/[barrel] on July 6 in the aftermath of the ‘no’ vote in Greece on the economic program, as well as lingering concerns about lower economic growth in China, higher oil exports from Iran, and continuing growth in global petroleum and other liquids inventories.”

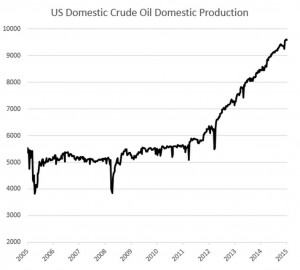

The key theme there is oversupply, and the warning signals have been flashing for some time now.

Oil inventories remain near the highest levels for this time of year in about 80 years, even though they had recently declined for eight straight weeks, a streak that was only broken last week.

In a note last month, Morgan Stanley’s Adam Longson noted that even with peak summer demand, there were still oil tankers sitting on the Atlantic, waiting to be bought.

Longson’s concern was that when seasonal demand dies down, it would be even harder to get rid of all the stockpiles that should have been sold.

And then there’s Iran.

Iran is in negotiations with the US and other countries over its nuclear program. If sanctions that have been imposed since 2012 are lifted, Iran could pump up to 400,000 extra barrels per day.

It’s not a game changer to the 90 million-barrel-per-day oil market, as PIMCO points out. But it’s not nothing, either.

Another anecdote of the oil glut came through the surge in the cost of oil tankers. Back in May we highlighted a Bloomberg report showing that the daily rate of oil supertankers surged to the highest level in seven years on a sudden rise in demand from producers.

But the US is not the only one doing all the pumping. It’s an open secret in the industry that the 12-member oil cartel OPEC is pumping more oil than its official target of 30 million barrels per day; in fact, it has for the past year.

One sign of a drawdown in production has come in the EIA’s short-term forecast, which projects that US production peaked in May and will decline sequentially through 2016. Still, this remains a forecast.

And so even though this week’s crash came suddenly, and while it coincided with a global selloff on concerns about Greece, it was long overdue.

Recent Comments